Narwhal tusks are a tale with a twist

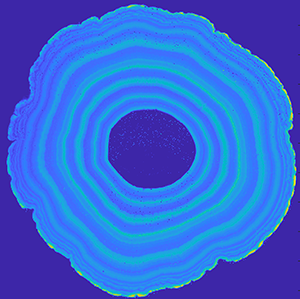

The narwhal’s spiral tusk has annual rings, and they can reveal changes in the climate. Researchers have just discovered that there also appear to be rings within the annual rings, which can provide even more details about living conditions in the Arctic.

“Narwhals are simply fascinating and impressive animals. It’s the most important driving force for researching this animal,” says Henrik Birkedal from Aarhus University, who leads the interdisciplinary project Narwhal tusks: A tale with a twist.

In this project, a Nordic team of researchers from Sweden – led by Marianne Liebi from Chalmers University of Technology, Greenland – led by Mads Peter Heide Jørgensen from the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources (Pinngortitaleriffik), and Denmark – led by Henrik Birkedal from Aarhus University, is working together to study the spiral tusks of narwhals. They are studying each individual layer of growth in the tusks of whales in Northwest Greenland, hoping to find answers to what the tusks can tell us about living conditions and climate conditions in the Arctic.

The researchers have recently made quite a surprising discovery:

“We’ve realised that the tusk structure is more complicated than we’d imagined. It also appears that within an annual growth period there are sub-patterns, sort of seasonal rings within the annual rings. We’ve just discovered that, and it looks very exciting. If we can get information that tells us that something happened in the living conditions of the narwhal in the month of April, it’ll be incredibly exciting,” says Henrik with excitement in his voice.

Throughout the narwhal’s lifetime, information on prey and environmental conditions get stored in the tusk. As the tusk grows, chemical elements get embedded, especially zinc and strontium. By looking at the components of the tusk through advanced scanners, the researchers can determine how much food was available during a certain period and what the living conditions were like.

X-ray instruments worth billions

The Greenlandic researchers in the project work from an Arctic research station in the Scoresby Sund fjord, and they fit the narwhals with radio transmitters and monitor them with drones to study their behaviour patterns. Meanwhile, Henrik and his Danish colleagues are studying the tusks from 20 narwhals that have been killed to be eaten. So, the tusks are surplus material.

Together with the researchers in Sweden, they are investigating how the tusk is shaped from birth until it becomes up to three metres long in the oldest narwhals.

“Initially, we received narwhal skulls frozen and visited the Forensic Medicine Institute in Denmark, where we put the skulls in a CT scanner. We were also allowed to visit and use MAX-IV – an extremely large X-ray machine in Lund, Sweden – as well as visit other places in Europe where we could get high-resolution scan images. We then cut the skulls into smaller pieces and scanned them again. That way we can hopefully form a complete picture of how the tusk was formed,” says Henrik Birkedal.

An interdisciplinary approach produces better results

In order to dig into the narwhals’ treasure trove, the project has combined the strengths of a variety of research disciplines. Henrik himself has a background in materials chemistry, while the Greenland Institute of Nature has knowledge of biology, and the Swedish researchers have a background in physics. According to Henrik, the interdisciplinary approach to narwhals is absolutely necessary to find the answers they are looking for:

“With my background in chemistry, I can make hypotheses about structures in the narwhals’ tusks, but my hypotheses have to be tested by others. We benefit greatly from learning from each other’s professional approaches. For those of us who aren’t biologists, it’s almost impossible to get hold of the tusks and also to be sure that we’re studying them in the right way,” he says and continues:

“We could go down to a shop and buy a tusk, but that won’t give us the answers we’re looking for, and no good science would come of it. Conversely, it’s valuable for biologists that we chemists have techniques available to examine the material of the tusks. In this way, we all win from this joint interdisciplinary collaboration.”

Narwhals contribute to a common Nordic history

It isn’t only researchers who benefit from the collaboration. According to Henrik, there is Nordic added value in the study of narwhals, which benefits the entire Nordic population.

One of the very significant aspects of Nordic added value is that narwhals are unique to our part of the world because they only live in the northern part of the Atlantic Ocean and play an active role in the Arctic environment.

Henrik Birkedal.

"They have also played a culturally historical role in the Nordic countries over time. We also hope to be able to convey the fascinating story of the narwhals and spread knowledge across the Nordic countries. We have a desire to produce a touring exhibition in the Nordic countries to draw attention to the fact that we have a common Nordic culture, science and history, which is connected across the Nordic countries,” concludes Henrik.