The black building soars over the landscape. Here, just outside Klaksvik, the Faroe Islands’ second largest city, is the salmon farming producer Bakkafrost. The snow is falling quietly and the clouds are hanging low. Black sheep are grazing around the building, which is built at the foot of a mountain, right down to the water’s edge. Bakkafrost is the largest of the Faroe Islands’ three salmon producers. Altogether, fish farming accounts for 45 percent of the Faroe Islands’ total exports.

Heidi Mortensen is a PhD student at the state-owned Fiskaaling, Aquaculture Research Station of the Faroes. She’s involved in the NordForsk-funded project DigiHeart, which conducts research into sustainable aquaculture.

“There are farming facilities in almost every single fjord in the Faroe Islands, so it’s a huge industry up here, and we’re very concerned about how aquaculture is affecting our ecosystem. Salmon farming accounts for almost half of our total exports, so the well-being of the fish is of the utmost socio-economic importance for the Faroe Islands.”

In DigiHeart, researchers from Norway, Sweden and the Faroe Islands are investigating why so many farmed fish die each year and whether the cause is heart conditions. In the Faroe Islands, the total mortality rate is almost 14 percent, amounting to an annual loss of DKK 800 million. In Norway, the mortality rate is up to 20 percent.

All farmed salmon are heart patients

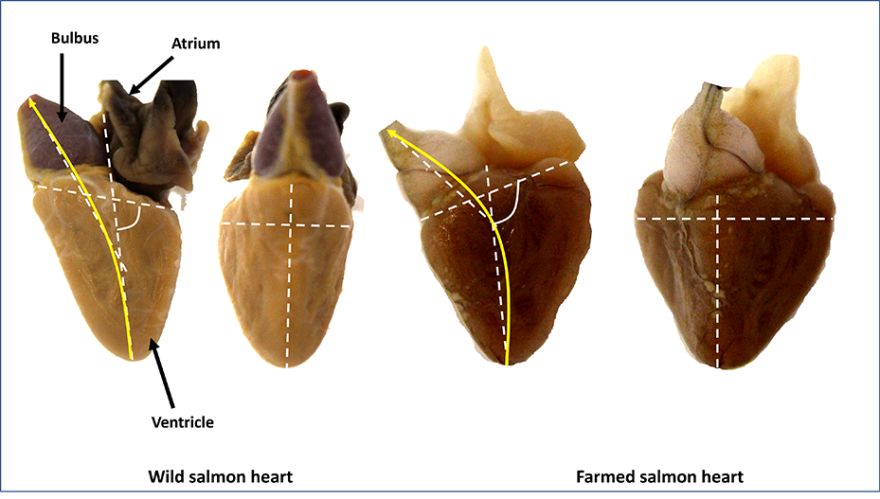

Heidi’s contribution to the project is to examine 800 salmon hearts acquired from the Faroese breeders. The hearts from farmed salmon differ significantly from those of wild salmon. The wild salmon have triangular hearts, which enable the fish to function even with a high heart rate. In other words, it has a heart shape that supports the type of living conditions it has. The heart of a farmed salmon, on the other hand, has a more rounded shape. The heart is more relaxed and doesn’t work as well, which is why it’s more vulnerable to stress. Farmed salmon are susceptible to stress more than wild salmon, as they are exposed to transport, repeated delousing and other stressful actions.

“Our results suggest that there may be several reasons why farmed salmon suffer from heart conditions. One reason may be that farmed salmon grow too fast and the heart doesn’t have enough time to develop correctly but gets deformed. Another reason could be that the stress they’re exposed to damages the heart. Ida Beitnes Johansen, who is the project leader of DigiHeart and one of my PhD supervisors, put it so well: ‘If all farmed salmon came to the hospital, they would all be treated for heart conditions.’ That’s how widespread the problem is,” says Heidi.

Images of the 800 Faroese salmon hearts have been sent to Norway, where computers automatically decode the hearts and observe the state they are in. In the project, they also compare the Faroese salmon hearts with their Norwegian counterparts to see if there are differences between them. In her PhD, Heidi Mortensen is examining 400 hearts for arterial sclerosis, which is a narrowing of the coronary artery that goes around the heart and supplies the heart muscle with oxygen and nutrients.

“We can see that many of the 400 salmon have a narrowing inside the heart. It’s natural for salmon to have it because it’s part of the salmon’s life, but there’s a higher frequency in farmed salmon than in wild salmon. The question is, why so? Perhaps they grow too quickly, but it could also be due to a stress response in connection with repeated delousing. We expect to see fewer cases in the fish that haven’t been deloused.”

Faroese farming differs from the rest of the Nordic Region

Compared to the other Nordic and Baltic countries, Faroese aquaculture is different in several respects. “Here we’re experts in keeping the fish on land for longer than in the other Nordic countries. We do this because there are considerable dangers out at sea in the form of diseases that can’t be controlled and parasites (salmon lice). When you delay putting the salmon into the sea, the salmon is exposed to the dangers for a shorter period. It’s also believed that the fish do better and become more robust by being put out into the open sea a little later,” Heidi explains.

In the Faroe Islands, for the past 20 years, fish have also been kept on land in RAS (recirculation aquaculture systems), where the water is purified and reused with very good results, whereas in Norway they mostly use the flow-through system, which means that the water is constantly replaced in the pools. The water parameters, such as the temperature, can be controlled much better in RAS than in flow-through systems. The temperature is very important for how fast the fish grows and its effect on heart health. It’s often said that production has generally been less intense in the Faroe Islands than in countries such as Norway.

“That’s why it’s very important that the Faroe Islands participate in this NordForsk project, as we can investigate whether our production method results in fewer heart problems compared to, say, Norway,” she says.

“You’ll never have zero mortality, because there will always be diseases and storms that the fish are exposed to. Those can’t be avoided. But anything under six-percent mortality should be doable. The current 14 percent is too high, but at one point it was up to almost 20 percent, so we know that the mortality rate can be decreased,” concludes Heidi.

Reportages from the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands are part of the Kingdom of Denmark and are located in the North Atlantic between Iceland and the Shetland Islands.

NordForsk went to the Faroe Islands to understand the importance of Nordic research co-operation for the Faroese.

This is the third part in the series.