A central idea in the research project Life at the Frontier, funded by NordForsk and the Economic and Social Research Council, is that there are barriers to integration. As a part of the work, the researchers in the project aim to help local policymakers to understand the complexity of issues connected to social frontiers and to tailor the provision of support and services.

Professor Gwilym Pryce from the University of Sheffield, who is leading the Life at the Frontier project, explains social frontiers in this way:

“A social frontier occurs when you have two communities that are next to each other and they are segregated in the sense that there's a high concentration of, say, Welsh people in a neighbourhood right next to a neighbourhood that mainly consists of English people. Crucially, and this is where the social frontier comes in, there is a border between those groups. It's not a gradual border, but it's an abrupt border. It's like a cliff edge, in social space.”

“Early on we realised that, even though there are lots of papers on residential segregation, using lots of different measures, this idea of what happens at the border between two communities hasn't really been explored very much, especially in terms of statistical analysis. As well as contributing to the quantitative research literature on social frontiers, we have also tried to develop a theoretical foundation for this area.”

Pryce explains that social frontiers might be important for several reasons. One is that they might reveal underlying tensions between two groups:

“Imagine you've got two communities next to each other. There may be very positive reasons for segregation, and very positive reasons for why we get a concentration of perhaps a particular ethnic group in a neighbourhood. We tend to be drawn to people like ourselves, people that we identify with and have similar language, religion etcetera.”

“The question raised by social frontiers is why doesn't anyone want to live near the boundary between two groups? So, social frontiers might indicate that there's an aversion to living near the out-group, and that might be more concerning than segregation per se.”

The article continues below the photo.

Photo: Private.

Located in the United Kingdom, Pryce highlights the division between Catholics and Protestants in Belfast as an extreme example of an absolute cliff edge between two groups, with community boundaries sometimes lying along the middle of a road. Such boundaries can evoke territorial tendencies, tendencies that are there latent in us, even if we are not aware of it:

“When I was a child, we lived in a house where we had a shared lawn between our house and our neighbour, but nothing indicated where our side of the lawn ended, and we happily mowed each other's lawns. Years later, I moved to a house where we had a fence down the middle, splitting the two gardens. And it was a completely different psychology. Anything that came over, like a branch from a neighbour's tree, felt like an intrusion. It was like, oh my goodness, they're invading our garden. So, I think, our sense of territorial area becomes much more distinct when there is a clear demarcation.”

The impact of social frontiers

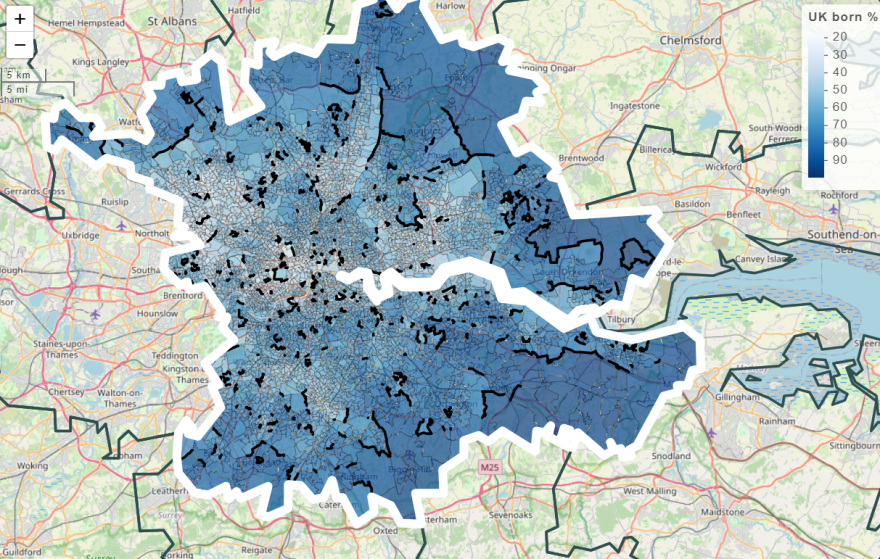

In addition to the theoretical part of the research, Pryce and his colleagues have tried to estimate where these social frontiers are located in towns and cities across the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Norway. They have also interviewed local residents about the presence and impact of social frontiers in their lives.

“It's one thing to estimate social frontiers using data on your computer, but we wanted to understand what they mean on the ground. So, we talked to people in local communities in Sweden, Norway, and the United Kingdom, showed them random boundaries on a map and asked them where they see the boundaries lie between areas. We asked them to choose ones that they thought corresponded to where they saw the boundaries lie. We didn't show them our estimated social frontiers because we wanted to see whether our estimates had any meaning or not to people living near them. Interestingly, this experiment provided a clear verification of our statistical estimates: the boundaries they selected corresponded very closely to the social frontiers we'd computed from the data. The in-depth interviews with these residents also revealed how frontiers and territoriality affects their everyday lives, potentially reinforcing cultural and social divisions.”

The researchers also found that there is evidence of estate agents reinforcing these divisions, steering ethnic minorities away from the most desirable neighbourhoods in terms of having the best opportunities and where you're most likely to flourish as a child, and where you are more likely to go to the university and have a successful job.

“Being steered away from those neighbourhoods can have a long-term effect on social mobility and the progress in your life."

The article continues below the illustration.

The vision

So how should societies address the issue of social frontiers? Pryce says that there is no easy solution, but one of the things the researchers have tried to do is to engage local communities and authorities on how to bridge that divide, instead of just sitting behind a computer analysing the data.

“By talking to people in different communities and sharing our results, it has become clear that social frontiers are a useful starting point for a conversation on how we got to this point as a society, why is it that nobody wants to live at the frontier and what it means for our behaviour in terms of avoiding each other and even avoiding walking through areas that you know are outside your territory.”

“What I’ve been quite surprised by and encouraged by is the desire to have this dialogue across communities and I think also there is a desire and a feeling that that there's a disconnect between policymakers, local authorities, and the police on some of these issues. It's almost like the state has been withdrawing from these areas and issues, because they're too difficult and too sensitive to handle. I really feel there is an important role for researchers to have on a local level, particularly through community engagement,” he says.

“Ultimately, our goal is three-fold. We want to contribute to theory and to lay a foundation for the conceptual framework that will help catalyse research in this area. Secondly, we want to advance the quantitative and qualitative analysis to provide methods and data for other researchers to develop practical resources for further research. And, thirdly, we want to contribute to impact and engagement in local communities through discussions with residents and policymakers.”

The Life at the Frontier project is a part of the Joint Nordic-UK research initiative on Migration and Integration.