Authors: Carina Mood and the IntegrateYouth team

Project: Structural, cultural and social integration among youth:

A multidimensional comparative project (IntegrateYouth)

Among the large numbers of refugees now forced to leave Ukraine are many children and young people. They face disruptive and stressful experiences of war, displacement, and in many cases the loss of friends and family members. Their future is uncertain, and many of these young people may have to settle long-term or even permanently in other countries. How are their lives likely to unfold? What can our countries do to support their development? In our NordForsk-funded project IntegrateYouth, we study the lives of young people from immigrant backgrounds in several European countries. We believe that the knowledge we’re building is helpful for understanding how to facilitate the development of Ukrainian children and young people who are about to settle in the Nordic countries.

Given the extremely stressful experiences, a prime concern is the mental health of refugee children. This is a concern upon arrival, and quick and efficient routes to safety and stability are important for both children and parents. Our research shows, however, that in the longer term the majority of children in migrant families show remarkable resilience. In their teenage years, their mental wellbeing, self-rated health and optimism for the future are, on average, as strong – or even stronger – among young people from war-torn countries as for young people in their host country’s majority population (Mood, Jonsson & Låftman 2016; 2017; Jonsson, Mood & Treuter 2022). We’ve not studied rarer, more extreme health problems, so we cannot rule out different patterns in these cases, although it is still important to emphasise that the long-term situation in this regard is good for the vast majority.

Social integration, that is, making friends, is a challenge for newly arrived immigrant children. In the first two to three years after immigration, they have on average fewer friends than other children, and are more often socially isolated (Hjalmarsson & Mood 2015; Plenty & Jonsson 2017). This pattern seems to hold regardless of national background. A reassuring finding is that, after a few years, these difficulties have ceased. However, from a child’s ‘here-and-now’ perspective, lacking friends is an important problem, even if temporary.

In the Nordic countries, the socioeconomic situation of refugees is good compared to the situation in many other destinations, and for many refugees better in an absolute sense compared to their origin country. Refugees are guaranteed benefits in kind and income support that keeps severe material deprivation at bay even when they have not yet been integrated into the labour market. As long as families are dependent on social benefits they are, however, likely to have an income that is relatively low in the host country. The most tangible consequence is probably the size and location of housing, as limited economic resources shrink the opportunities on the housing market. The quality of housing in terms of equipment and modernity is, however, likely to be high overall, as the housing stock in the Nordic countries is of high quality in an international context. There is only a weak correlation between family incomes and children’s own economic resources, and our research suggests that children’s average economic resources are not lower for children and young people in immigrant families. They report equal levels of own ‘income’ (from parents and work), equal access to a cash margin if in need, and no more problems than others in being able to afford to take part in activities with friends (Mood & Jonsson 2013; Mood 2018). Hence, the socioeconomic situation is unlikely to be a major concern.

Schooling is crucial for children’s lives and development. Overall, children and young people from an immigrant background – even those born to immigrant parents in the host country – tend to have weaker school results. At the same time, they have much higher aspirations and place more importance on education (Friberg 2019; Rudolphi & Salikutluk 2021). Nordic school systems are comprehensive and offer free-of-charge tuition, with little performance-based tracking. This means that young people from immigrant backgrounds are not held back and their high aspirations are allowed to play out. The higher average aspirations and lower average performance combine to create a ‘bimodal’ distribution: Young people from immigrant backgrounds are equally likely as those with Swedish-born parents to get a tertiary (university or university college) degree. At the other end of the distribution, however, young people from immigrant backgrounds have a marked over-risk of ending up with very low education, that is, lacking an upper secondary school qualification – often because their grades from compulsory school are so weak that they do not qualify for upper secondary school education (Jonsson, Mood & Treuter 2022).

A crucial factor in relation to education is age at migration. Those who immigrate after around the age of nine are at a particularly high risk of ending up with low grades and low education (Hermansen 2017; Jonsson, Mood & Treuter 2022), and this pattern holds regardless of national origin, and for both boys and girls. Even with extensive opportunities for remedial education, for example in the Swedish Komvux system, only half of those who immigrate to Sweden in their early teenage years manage to get an upper secondary school qualification (Jonsson, Mood & Treuter 2022).

In seeking to learn from earlier migrant experiences, diversity among migrants must be acknowledged. Averages and typical experiences for an undifferentiated group of ‘migrant youth’ may not be particularly relevant for understanding the specific challenges that Ukrainian children and young people are likely to face. An important strength of the IntegrateYouth project is that migrant diversity is weaved into its design as a fundamental premise. In most domains we have observed greater challenges the greater the distance is between the old and the new country in terms of the population’s education, language, religion, and culture. For Ukrainians, many factors speak in their favour: Being a non-visible minority, they are less likely than many other migrants to be stigmatised and discriminated against, which in turn is likely to benefit social and socioeconomic integration as well as mental health. Many Ukrainians are also highly educated, which facilitates socioeconomic integration and also helps their children’s school achievement.

Although Eastern European/ex-USSR migrants to Sweden may seem to be an obvious group to learn from, the fact that they are generally not refugees, and strongly self-selected, makes drawing comparisons difficult. We believe that children and young people who migrated from ex-Yugoslavia during the 1990s (mostly Bosnians) are a better comparison group, as they share many of the features of the Ukrainian group today, primarily the experience of flight from war and large-scale violence. Both are also non-visible minorities of European origin, speaking (in most cases) a Slavic language, and having parents with, on average, high education relative to refugees from most other regions. There are, however, also a couple of potentially significant differences. First, religion: While many refugees from ex-Yugoslavia (especially Bosnia) were Muslims, Ukrainians are predominantly of an orthodox Christian denomination. Second, in the 1990s a large Yugoslavian community already existed in Sweden (following earlier waves of labour migration), meaning that for those who came to Sweden there were networks to connect to, and also a support system in the Serbo-Croatian language (e.g., news broadcasts and mother-tongue teaching).

So how has the situation for migrants developed after almost 30 years since the wars in Yugoslavia? In Sweden, adults as well as children in this immigrant group have enjoyed good socioeconomic development, with adult employment levels after a few years reaching that of the majority population (this process being quicker for those who settled in areas with more jobs) (Ekberg 2016). Results from Norway show a similar positive development (Bratsberg, Raaum & Røed 2017). Given the similarity of the groups’ characteristics, it is likely that the Ukrainian migrants, if they remain, will see a similar development. In fact, their opportunities for labour market integration are likely greater than for the ex-Yugoslavians, due to the triggering of the provisions in the EU 2001 Temporary Protection Directive. This directive was created following the Balkan wars as the EU realised that the ordinary asylum procedures did not fit situations with large-scale exodus from violence. Among other things, it gives Ukrainan migrants instant access to EU labour markets without having to wait for an asylum decision.

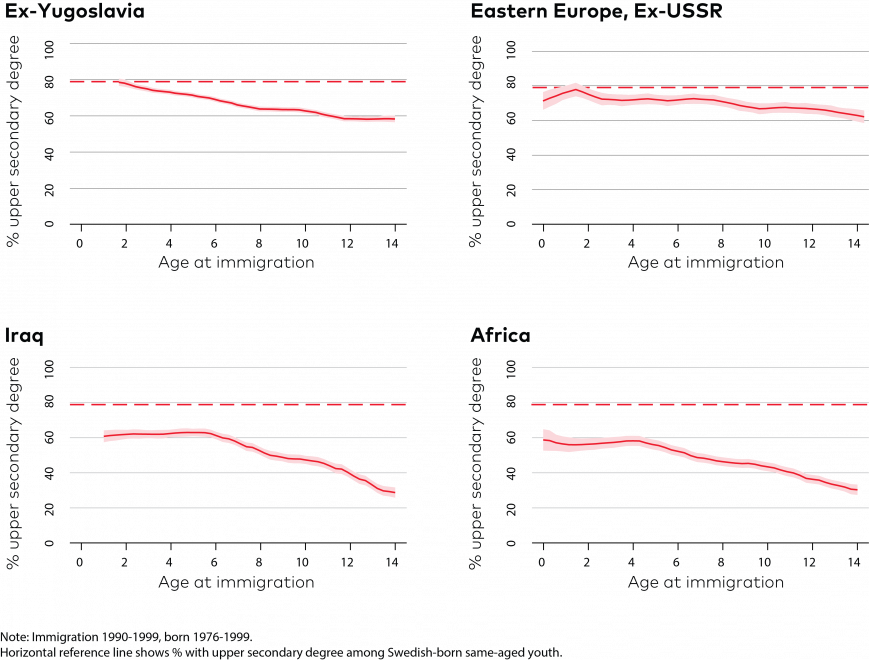

Ex-Yugoslavians who immigrated as children have succeeded well in education compared to non-European migrants, but, just as for other migrant groups, many of those who immigrated later in their childhood did not obtain an upper secondary school qualification. Figure 1 shows the proportion of immigrant children who had an upper secondary school qualification by age 20 according to their age at immigration, distinguishing four relatively big origin regions. On average, children from all four regions suffer a disadvantage compared to children with Swedish-born parents (where just under 80% in these cohorts obtained an upper secondary school qualification, indicated by the dashed reference line), and in all four cases we see that the disadvantage increases with their age at immigration. This suggests that the age-at-migration-effect is likely generic. However, Figure 1 also illustrates another important point: The level of disadvantage differs depending on origin. For example, among children who immigrate at age 14, 60% of those of ex-Yugoslavian or Eastern European/ex-USSR origin manage to get an upper secondary school qualification, compared to 35% of those of Iraqi or African origin.

In Figure 2, we can see that not only is there systematic variation across groups from different origin regions, there is also a systematic difference in educational success between boys and girls. Boys suffer more than girls from immigrating at an older age: For example, among ex-Yugoslavians who immigrated at age 14, just over half of the boys got an upper secondary school qualification, compared to over 60% among the girls.

How can our knowledge assist Nordic countries in helping Ukrainian children?

First, the systematic evidence (from our research group and others) that children from immigrant backgrounds (including refugees) have, on average, very high aspirations and a remarkable capacity to remain healthy, optimistic and achievement-oriented despite stressful experiences means that it is imperative that they be seen as active and capable co-creators of their futures. Policies and support must have a child perspective that emphasises the agency and potential of refugee children.

Second, children arriving in late childhood – and in particular boys – need special attention and intense school support. While many of these children will succeed in school, the risk is high that a significant minority will not. There is no time to lose here: Study and (host-country) language support for older children should be given high priority and commence as soon as practically possible. The EU Temporary Protection Directive gives a right to education for children, so any barriers here are practical rather than legal. Resources should be earmarked so that schools with many older immigrant students receive sufficient resources. Children’s transition from the Ukrainian to the host-country school system may be facilitated by employing teacher-educated Ukrainians in a supporting role.

Third, recent immigrant children and young people often need support with opportunities to establish friendships, in school and outside. Teachers and civil society organisations should actively, but respectfully, organise activities in ways that make it easier for newcomers to establish contacts.

Fourth, settlement for migrants must balance the understandable desire for co-ethnic contacts with housing availability and job opportunities. Many refugees from ex-Yugoslavia to Sweden settled close to co-ethnics in Malmö, where unemployment was high. Ekberg (2016) shows that these refugees took longer to get established in the labour market than those of the same background who settled in communities with better labour markets. Parents’ establishment in the labour market is indirectly important for children and young people as it gives the family more independence and better chances in the housing market.

Fifth, we do not yet know how many children and young people will stay and how many will return to Ukraine. We know from previous experience in the Nordic countries that few refugees return to their country of origin, and this holds also for refugees from ex-Yugoslavia. Nevertheless, a two-pronged strategy is probably sensible: We should support positive development in the Nordic context, but also acknowledge the importance of children’s co-ethnic networks and maintenance and development of their mother tongue.

References

- Bratsberg, B., Raaum, O., & Røed, K. (2017). Immigrant labor market integration across admission classes. Nordic Economic Policy Review 2017: 17–53.

- Ekberg, J., (2016). Det finns framgångsrika flyktingar på arbetsmarknaden. Ekonomisk debatt, 44(5), 6–11.

- Friberg, J. H., (2019). Does selective acculturation work? Cultural orientations, educational aspirations and school effort among children of immigrants in Norway. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45(15): 2844–2863.

- Hermansen, A. S., (2017). Age at arrival and life chances among childhood immigrants. Demography 54(1): 201–229.

- Hjalmarsson, S., & Mood, C. (2015). Do poorer youth have fewer friends? The role of household and child economic resources in adolescent school-class friendships. Children and Youth Services Review, 57, 201–211.

- Mood, C., (2018). “Keeping up with the Smiths, Müllers, De Jongs, and Johanssons – The Economic Situation of Minority and Majority Youth” Kapitel 4 in Kalter, F., Jonsson, J. O., van Tubergen F., & Heath, A. (red.) Growing up in Diverse Societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mood, C., Jonsson, J. O., & Låftman, S. B., (2016). Immigrant integration and youth mental health in four European countries. European Sociological Review 32(6): 716–729.

- Mood, C., Jonsson, J. O., & Låftman, S. B., (2017). Immigrant youth’s mental health advantage: The role of family structure and relations. Journal of Marriage and Family 79 (April): 419–436.

- Jonsson, J. O., Mood, C., & Treuter, G., (2022). Integration av unga: En mångkulturell generation växer upp. Stockholm: Makadam förlag.

- Mood, C. & Jonsson, J. O., (2013). Ekonomisk utsatthet och välfärd bland barn och deras familjer 1968–2010. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen.

- Plenty, S. & Jonsson, J. O., (2017). Social Exclusion among Peers: The Role of Immigrant Status and

- Classroom Immigrant Density, Journal of Youth and Adolescence 46: 1275–1288.

- Rudolphi, F. & Salikutluk, Z., (2021). Aiming high no matter what? Educational Aspirations of Ethnic Minority and Native Youth in England, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden. Comparative Sociology 20(1): 70–100.